Acritarchs are known from 1400 Ma and had achieved considerable diversity by 1300 Ma. Diversity crashed during the Sturtian glacial event around 800 Ma. Diversity increased again during the Ediacaran period. Diversity declined suddenly at the end of the Precambrian. The acritarchs show their greatest diversity during the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian. The nature of some Acritarchs can be identified by their structure. A few can be tentatively identified by the presence of specific chemicals associated with the fossils.

The albedo is a measure of reflectivity of a surface or body. It is the ratio of electromagnetic radiation reflected to the amount hitting it. The fraction, usually expressed as a percentage from 0% to 100%, is an important concept in climatology. This ratio depends on the frequency of the radiation considered: but in general it refers to an average across the spectrum of visible light. It also depends on the angle of incidence of the radiation. Fresh snow albedos are high: up to 90%, whereas, the ocean surface has a low albedo.

The "classical" example of albedo effect is the snow-temperature feedback. If a snow covered area warms and the snow melts, the albedo decreases, more sunlight is absorbed, and the temperature tends to increase even more. The converse is also true: if snow lies upon the ground, a cooling cycle occurs, because more sunlight is reflected back into space. So great is the range of albedos from ice that some scientists here are using it to classify ice types. Some actual measurements that include the albedo of bubbly ice are found here.

The algae (singular alga) consist of several different groups of living organisms that capture light energy through photosynthesis, converting inorganic substances into simple sugars with the captured energy. Algae have been traditionally regarded as simple plants, and some are closely related to the higher plants. Others appear to represent different protist groups, alongside other organisms that are traditionally considered more animal-like (protozoa). Thus algae do not represent a single evolutionary direction or line, but a level of organization that may have developed several times in the early history of life on earth.

Algae range from single-celled organisms to multi-cellular organisms, some with fairly complex differentiated form and (if marine) called seaweeds. All lack leaves, roots, flowers, and other organ structures that characterize higher plants. They are distinguished from other protozoa in that they are photoautotrophic, although this is not a hard and fast distinction as some groups contain members that are mixotrophic, deriving energy both from photosynthesis and uptake of organic carbon either by osmotrophy, myzotrophy, or phagotrophy. Some unicellular species rely entirely on external energy sources and have reduced or lost their photosynthetic apparatus.

All algae have photosynthetic machinery ultimately derived from the cyanobacteria, and so produce oxygen as a by-product of photosynthesis, unlike the non-cyanobacterial photosynthetic bacteria.

Algae are usually found in damp places or bodies of water and thus are common in terrestrial as well as aquatic environments. However, terrestrial algae are usually rather inconspicuous and far more common in moist, tropical regions than dry ones, because algae lack vascular tissues and other adaptions to live on land. Algae can endure dryness and other conditions in symbiosis with a fungus as lichen. The various sorts of algae play significant roles in aquatic ecology. Microscopic forms that live suspended in the water column—called phytoplankton—provide the food base for most marine food chains. In very high densities (so-called algal blooms) they may discolor the water and outcompete or poison other life forms. The seaweeds grow mostly in shallow marine waters. Some are used as human food or are harvested for useful substances such as agar or fertilizer. The study of algae is called phycology or algology.

Anoxia is a condition in which there is an absence of oxygen.

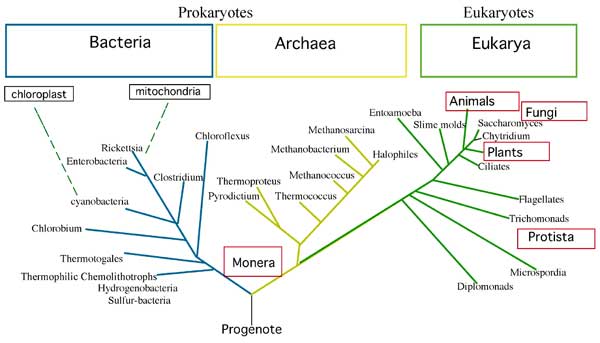

Archaea were identified in 1977 by Carl Woese and George Fox based on their separation from other prokaryotes on rRNA phylogenetic trees. These two groups were originally named the Archaebacteria and Eubacteria and treated as kingdoms or subkingdoms. Woese argued that they represented fundamentally different branches of living things. He later renamed the groups Archaea and Bacteria to emphasize this, and argued that together with Eukarya they comprise three domains of living things.

Archaea are similar to other prokaryotes in most aspects of cell structure and metabolism. However, their genetic transcription and translation - the two central processes in molecular biology - do not show the typical bacterial features, but are extremely similar to those of eukaryotes. For instance, archaean translation uses eukaryotic initiation and elongation factors, and their transcription involves TATA-binding proteins and TFIIB as in eukaryotes.

Several other characteristics also set the Archaea apart. Unlike most bacteria, they have a single cell membrane that lacks a peptidoglycan wall. Further, both bacteria and eukaryotes have membranes composed mainly of glycerol-ester lipids, whereas archaea have membranes composed of glycerol-ether lipids. These differences may be an adaptation on the part of Archaea to hyperthermophily. Archaeans also have flagella that are notably different in composition and development from the superficially similar flagella of bacteria.

Many archaeans are extremophiles. Some live at very high temperatures, typically above 100°C, as found in geysers and black smokers. Others are found in very cold habitats or in highly saline, acidic, or alkaline water. However, other archaeans are mesophiles, and have been found in environments like marshland, sewage, and soil. Many methanogenic archaea are found in the digestive tracts of animals such as ruminants, termites, and humans. Archaea are usually harmless to other organisms and none are known to cause disease. Learn more?

Bacteria (singular, bacterium) are a major group of living organisms. Most are microscopic and unicellular, with a relatively simple cell structure lacking a cell nucleus, and organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts, in contrast to organisms with more complex cells, called eukaryotes. The term "bacteria" has variously applied to all prokaryotes or to a major group of them, otherwise called the eubacteria, depending on ideas about their relationships.

Bacteria are the most abundant of all organisms. They are ubiquitous in soil, water, and as symbionts of other organisms. Many pathogens are bacteria. Most are minute, usually only 0.5-5.0 ?m in their longest dimension, although giant bacteria like Thiomargarita namibiensis and Epulopiscium fishelsoni may grow past 0.5 mm in size. They generally have cell walls, like plant and fungal cells, but with a very different composition (peptidoglycans). Many move around using flagella, which are different in structure from the flagella of other groups.

Bacteria are the most abundant of all organisms. They are ubiquitous in soil, water, and as symbionts of other organisms. Many pathogens are bacteria. Most are minute, usually only 0.5-5.0 ?m in their longest dimension, although giant bacteria like Thiomargarita namibiensis and Epulopiscium fishelsoni may grow past 0.5 mm in size. They generally have cell walls, like plant and fungal cells, but with a very different composition (peptidoglycans). Many move around using flagella, which are different in structure from the flagella of other groups.

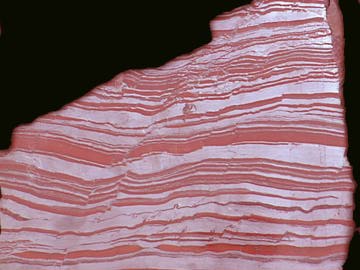

Banded Iron Formations are a distinctive type of rock occurring in old sedimentary rocks. The structures consist of repeated thin layers of iron oxides, either magnetite or hematite, with bands of shale and chert. Some of the oldest known rock formations dated around 3 billion years before present, include banded iron layers, and the banded layers are a common feature in sediments for much of the Earth's early history. Banded iron beds are less common after 1800Ma although some are known that are much younger.

The conventional concept is that the banded iron layers are the result of oxygen released by photosynthetic cyanobacteria, combining with dissolved iron in Earth's oceans to form insoluble iron oxides. The banding is assumed to result from cyclic peaks in oxygen production. It is unclear whether these were seasonal or followed some other cycle. It is assumed that initially the Earth started out with vast amounts of iron dissolved in the world's seas. Eventually, as photosynthetic organisms pumped out oxygen, all the available iron in the Earth's oceans was precipitated out as iron oxides. The atmosphere became oxygenated.

The conventional concept is that the banded iron layers are the result of oxygen released by photosynthetic cyanobacteria, combining with dissolved iron in Earth's oceans to form insoluble iron oxides. The banding is assumed to result from cyclic peaks in oxygen production. It is unclear whether these were seasonal or followed some other cycle. It is assumed that initially the Earth started out with vast amounts of iron dissolved in the world's seas. Eventually, as photosynthetic organisms pumped out oxygen, all the available iron in the Earth's oceans was precipitated out as iron oxides. The atmosphere became oxygenated.

Until fairly recently, it was assumed that the rare later banded iron deposits represent unusual conditions where oxygen was depleted locally and iron rich waters could form then come into contact with oxygenated water. An alternate explanation for these later rare deposits relates them to Snowball Earth in that the earth's free oxygen may have been nearly or totally depleted during the worldwide glaciations. Alternatively, some geochemists suggest that BIFs could form by direct oxydation of iron by autotrophic (non-photosynthetic) microbes.

The total amount of oxygen locked up in the banded iron beds is estimated to be perhaps 20 times the volume of oxygen present in the modern atmosphere. Banded iron beds are an important commercial source of iron ore.

Bilateral symmetry means that there is one plane of reflection. In biology, bilateral symmetry is a characteristic of multicellular organisms, particularly animals. A bilaterally symmetric, or bilaterian, organism is one that is symmetric about a plane running from its front to back, and has nearly identical right and left halves. View where bilaterian organisms sit in the tree of life here.

Boreal means northern (from the Greek, Boreas, god of the North Wind). The term boreal generally refers to ecosystems in subarctic climatic zones. Boreal forests, or taiga, represent the largest terrestial biome. Occuring between 50 and 60 degrees north latitudes, boreal forests occur in the broad belt of Eurasia and North America: two-thirds in Siberia with the rest in Scandinavia, Alaska, and Canada. Seasons are divided into short, moist, and moderately warm summers and long, cold, and dry winters.

Mikhail Ivanovich Budyko is a Belorussian scientist who was the first to calculate the balance of heat received from the Sun and radiated from the Earth's surface, checking his calculations against observational data from all parts of the world. In 1956 he published his results in Heat Balance of the Earth's Surface. This work changed climatology from a qualitative discipline, based on measurement of climatic data from all over the world, into a more physical discipline. Professor Budyko became a pioneer of physical climatology, adding to his 1956 book an atlas, completed in 1963, that shows the Earth as viewed from space with all aspects of the Earth's heat balance displayed. Calculations of climate change are based on this atlas.

By 1960, Professor Budyko was already concerned about the possibility of a general rise in world temperatures caused by human activity. He suggested the day might come when it became necessary to scatter particles in the stratosphere in order to reflect solar radiation and reduce the rate of temperature increase. In 1972, he was able to confirm a link between past climate changes and changes in the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (see also Svante Arrhenius ). He warned then that his analysis indicated a general warming of the world's climates due to the rise in the carbon dioxide concentration brought about by the increasing consumption of fossil fuels. His 1972 calculations predicted a rise in temperature of about 6.3° F (3.5° C) from this cause between 1950 and about 2070.

His studies of the effects on climate of altering the composition of the atmosphere led him, in the early 1980s, to ponder the climatic consequences of a large-scale thermonuclear war. He suggested that such a war might inject such a huge quantity of aerosols into the atmosphere that the entire world would be plunged into deep cold, a "nuclear winter" that might threaten human survival.

Mikhail Budyko was born on January 26, 1920, at Gomel, Belarus. He was educated in Leningrad and from 1942 until 1975 worked at the Main Geophysical Observatory, Leningrad, where he was the director from 1972 to 1975. He was then appointed head of the Division for Climate Change Research, at the State Hydrological Institute, St. Petersburg, the position he still holds. He was elected an Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1992.

He has been awarded many prizes, including the Lenin National Prize (1958), Gold Medal of the World Meteorological Organization (1987), A. A. Grigoryev Prize of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1995), and Blue Planet Prize (1999) for his contribution to environmental research.

Calcisponges are sponges that form skeletons made of calcite spicules

The Cambrian is a major division of the geologic timescale that begins about 542 Ma (million years ago) at the end of the Proterozoic eon and ended about 488.3 Ma with the beginning of the Ordovician period. It is the first period of the Paleozoic era of the Phanerozoic eon. The Cambrian is the earliest period in whose rocks are found numerous large, distinctly-fossilizable multicellular organisms that are more complex than sponges or medusoids. During this time, roughly fifty separate major groups of organisms or "phyla" (a phylum defines the basic body plan of some group of modern or extinct animals) emerged suddenly, in most cases without evident precursors. This radiation of animal phyla is referred to as the Cambrian explosion. You can see how 3000 of today's estimated 9 million species are related by viewing this pdf.

The Cambrian Explosion generally refers to the geologically sudden appearance of a number of new complex organisms between 543 and 530 million years ago (mya). Prior to the discovery of the Burgess Shale, fossil finds showed life on Earth consisting only of single-celled organisms or simple diploblastic fauna (two-layers of cells, allowing every cell to be in contact with its watery mineral-rich environment). Abruptly, many kinds of fossils appearing in the Burgess Shale show skeletal body features, where none had yet been found in the earlier fossil record.

More recent research shows that this adaptive radiation of animal phyla started about 30 million years earlier, around 570 mya, before the beginning of the Cambrian geologic period. In 1994, triploblastic animals (organisms with more than two layers, and who therefore rely on internal organs and systems for their cells' supplies of food and waste disposal), were discovered preserved as phosphatized embryos in rocks from southern China. These fossils are about 570 million years old and thus are even older than the Ediacaran fauna.

Cap carbonates are continuous layers of limestone (CaCO3) and/or dolostone (Ca0.5Mg0.5CO3) that sharply overlie Neoproterozoic glacial deposits, or sub-glacial erosion surfaces where the glacial deposits are absent. They occur world-wide, even in regions otherwise lacking carbonate strata. Sturtian (~700 Ma) and Marinoan (635 Ma) cap carbonates are lithologically distinct, and both have unusual traits (e.g., thick sea-floor cements, giant wave ripples, microbial mounds with vertical tubular structure, primary and early diagenetic barite, BaSO4) that distinguish them from standard carbonates. Marinoan cap carbonates are transgressive (i.e., inferred water depths increase with stratigraphic height) and most workers associate them with the flooding of continental shelves and platforms as ice sheets melted. Sturtian cap carbonates were mostly not deposited until after post-glacial flooding had taken place. The preservation of cap carbonates and related highstand deposits after isostatic adjustment (or post-glacial “rebound”) implies substantial erosion and/or tectonic subsidence during the glacial period. Post-Marinoan (Ediacaran and Phanerozoic) glaciations lack cap carbonates or they are poorly developed. See the page on cap carbonates to learn more

The choanoflagellates are a group of flagellate protozoa. They are considered to be the closest relatives of the animals, and in particular may be the direct ancestors of sponges. Most choanoflagellates are sessile, with a stalk opposite the flagellum. A number of species are colonial, usually taking the form of a cluster of cells on a single stalk. Of special note is Proterospongia, which takes the form of a glob of cells, of which the external cells are typical flagellates with collars, but the internal cells are non-motile. The choanocytes of sponges have the same basic structure as choanoflagellates. Collared cells are occasionally found in a few other animal groups, such as flatworms. These relationships make colonial choanoflagellates a plausible candidate as the ancestors of the animal kingdom. View where choanoflagellates sit in the tree of life here.

The Chromista are a eukaryotic supergroup, which may be treated as a separate kingdom or included among the Protista. They include all algae whose chloroplasts contain chlorophylls a and c, as well as various colorless forms that are closely related to them. The name Chromista was introduced by Cavalier-Smith in 1981; the earlier names chromophyte and chromobiont correspond to roughly the same group.

Cnidaria (from Greek knide=nettle) is a phylum containing about 10,000 species of relatively simple animals found exclusively in aquatic environments, with most being species being marine). Cnidarians get their name from cnidocytes, which are specialized cells that carry stinging organelles. Most corals belong here, as do the familiar sea anemones, jellyfish, sea pens, sea pansies and sea wasps. The names Coelenterata and Coelentera were formerly applied to the group, but as those names included the Ctenophores (comb jellies), they have been abandoned. Cnidarians are highly evident in the fossil record, having first appeared in the Precambrian era. View where cnidaria sit in the tree of life here.

Condensation is the change in phase of a substance to a denser phase, such as gas to a liquid. In the case of water, its vapor will only condense onto another surface when that surface is cooler than the temperature of the water vapor, or when the water vapor equilibrium in air has been exceeded. When water vapor condenses onto a surface, a net warming occurs on that surface. The water molecule brings a parcel of heat with it. In turn, the temperature of the atmosphere drops slightly. In the atmosphere, condensation produces clouds, fog and precipitation--usually only when facilitated by cloud condensation nuclei. The dew point of an air parcel is the temperature to which it must cool before condensation in the air begins to form. Also, a net condensation of water vapor occurs on surfaces when the temperature of the surface is at or below the dew point temperature of the atmosphere. Deposition is a type of condensation. Frost and snow are examples of deposition. Deposition is the direct formation of ice from water vapor.

The Cretaceous period is a divisions of the geologic timescale, entending from the end of the Jurassic period, about 146 million years ago (Ma), to the beginning of the Paleocene epoch of the Tertiary period (65.5 Ma). It is the third and final period in the Mesozoic era.

The Cryogenian Period (from Greek cryos "ice" and genesis "birth") is the second geologic period of the Neoproterozoic Era (the other is the Ediacaran Period). The Sturtian and Marinoan glaciations occured during this period and its timeframe is between 800 Ma and approximately 635 Ma.

The name is derived from the glacial deposits characteristic of the period, indicating that at this time, the Earth suffered its most severe ice ages in history, with glaciers extending to the equator on several occasions. These glaciations are represented by worldwide glacial deposits (called tillites). It is generally considered to be divisible into at least two (Sturtian around 800 Ma and Marinoan 650 Ma) major worldwide glaciations, with several other more localised glaciations. The tillite deposits occur also in places which were at low latitudes during the Cryogenian, which lead to the hypothesis of Snowball Earth.

The population of acritarchs crashed during the Sturtian glaciation and it is possible that oxygen levels in the atmosphere increased afterwards. There are a number of enigmatic features about Cryogenic glaciations, including indications of glaciation at very low latitudes and the presence of limestones -- sediments which are normally warm water -- directly above the glacial deposits, features now incorporated in the Snowball Earth hypothesis.

Cyanobacteria Greek: cyanos = blue) are a phylum of bacteria that obtain their energy through photosynthesis. They are often referred to as blue-green algae, even though it is now known that they are not directly related to any of the other algal groups, which are all eukaryotes. Nonetheless, the description is still sometimes used to reflect their appearance and ecological role.

Fossil traces of cyanobacteria are claimed to

have been found from around 3.8 billion years ago.

Fossil traces of cyanobacteria are claimed to

have been found from around 3.8 billion years ago.The cyanophytes lack flagella, but may move about by gliding along surfaces. Most are found in freshwater, but many are marine, occur in damp soil, or even temporarily moistened rocks in deserts. A few are endosymbionts in lichens, plants, various protists, or sponges and provide energy for the host. Some even live in the fur of sloths, providing a form of camouflage.

The photo on the right shows a huge cyanobacterial bloom in the Baltic Sea east of Sweden on Aug 2, 1999.

Deuterostomes (from the Greek=other mouth) are a superphylum of animals. They are a subtaxon of the Bilateria, and are opposite protostomes. Deuterostomes are distinguished by their embryonic development; in deuterostomes, the first opening (the blastopore) becomes the anus, while in protostomes it becomes the mouth. There are three phyla of deuterostomes: Chordata (vertebrates and their kin); Echinodermata (starfishes, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, etc.); and Hemichordata (acorn worms). View where Deuterostomes sit in the tree of life here.

The Ecdysozoa are a group of protostome animals, including the Arthropoda, Nematoda, and several smaller phyla. They were first defined in 1997 based mainly on phylogenetic trees constructed using 18S ribosomal RNA genes. However, the group is also strongly supported by morphological characters, and can be considered as including all animals that shed their exoskeleton. View where Ecdysozoa sit in the tree of life here.

The Ediacaran Period is the last geological period of the Neoproterozoic Era, just before the Cambrian. It ranges from approximately 635 to 542 million years before the present. Historically this name has been variously used by researchers, but its status as an official geological period was ratified in March 2004 by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) and announced on May 13, 2004, the first new such period declared in 120 years. See informative BBC article.

The period is unusual because its beginning is not defined by a change in the fossil record. Unusual soft bodied fossils do occur in the Ediacaran Period, but these are limited to the latter parts of the Period, after about 580 million years ago. Rather, the beginning is defined by the appearance of a new texturally and chemically distinctive carbonate layer that indicates a climatic change (the end of a global ice age). There is an unusual depletion of 13C that marks the end of the global ice ages of the preceding Cryogenian Period. The date of the boundary is fairly well constrained at 635 million years ago based on U-Pb (uranium-lead) dates from Namibia and China.

The name comes from the Ediacara Hills of South Australia, thus being the only geologic period to have a name originating in the southern hemisphere. It was in the Ediacara Hills that peculiar Precambrian fossils were found by the geologist Reg Sprigg in 1946, and studied by Martin Glaessner starting in the 1950s. Glaessner initially thought the creatures to be primitive versions of animals such as corals, sea-pens and worms that were better known from later times. In subsequent decades, many more Precambrian fossils have been found in South Australia. Additional fossils have been found in dozens of outcrops on all continents, and collectively these have come to be known as the Ediacaran biota. Especially important deposits have been found in the White Sea area of Russia, in southwestern Africa, in northwestern Canada, and in eastern Newfoundland.

An endosymbiont is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism, i.e. forming an endosymbiosis (Greek: endo = inner and biosis = living). For instance, some nitrogen fixing bacteria (known as rhizobia) live in root nodules on legume roots, reef-building corals contain single-celled algae, and several insect species contain bacterial endosymbionts. Many other examples of endosymbiosis exist.

Many instances of endosymbiosis, but not all, are obligate, where neither the endosymbiont nor the host can survive without the other, such as gutless marine worms which get nutrition from their endosymbiotic bacteria. Also, some endosymbioses can be harmful to either of the organisms involved. Nowadays, it is generally agreed that certain organelles of the eukaryotic cell, especially mitochondria and chloroplasts, originated as bacterial endosymbionts and later became integral parts of their cell structure; but in the 1960's when Lynn Margulis first proposed the idea, it was extremely contentious.

Eskers are long, winding ridges of stratified

sand and gravel, which occur in glaciated and formerly glaciated regions. They

are frequently several miles in length and, because of their peculiar uniform

shape, somewhat resemble railroad embankments. Eskers

are the deposits left by streams which flowed under glaciers. After the ice melt

away, the stream deposits remain as long winding

ridges.

Eskers are long, winding ridges of stratified

sand and gravel, which occur in glaciated and formerly glaciated regions. They

are frequently several miles in length and, because of their peculiar uniform

shape, somewhat resemble railroad embankments. Eskers

are the deposits left by streams which flowed under glaciers. After the ice melt

away, the stream deposits remain as long winding

ridges.

A eukaryote (from the Greek eus=true and karyon=nut, referring to the cell nucleus) is an organism with complex cells, in which the genetic material is organized into membrane-bound nuclei. Eukaryotes comprise animals, plants, and fungi—which are mostly multicellular—as well as various other groups that are collectively classified as protists (many of which are unicellular). In contrast, other organisms, known as prokaryotes, lack nuclei and other complex cell structures. The eukaryotes share a common origin, and are often treated formally as a superkingdom, empire, or domain.

Eukaryotic cells are generally much larger than prokaryotes, typically a thousand times by volume. They have a variety of internal membranes and structures, called organelles, and a cytoskeleton composed of microtubules and microfilaments, which play an important role in defining the cell's organization. Eukaryotic DNA is divided into several bundles called chromosomes, which are separated by a microtubular spindle during nuclear division. In addition to asexual cell division, most eukaryotes have some process of sexual reproduction via cell fusion, which is not found among prokaryotes

Eumetazoa is a subkingdom of the animal kingdom comprising all animals except the sponges and the wormlike mezozoans.

A glacial erratic is a piece of rock carried by glacial ice some distance from the rock outcrop from which it came. Erratics can range in size from pebbles to massive pieces such as the Okotoks (16,500 tons) and Airdrie erratics found in Alberta, Canada. They can be found miles away from their original location.

Landslides or rockfalls initially dropped the rocks on top of glacial ice. The glaciers continued to move, carrying the rocks with it. When the ice melted, the erratics were left in their present locations.

Greenhouse gases are gaseous components of the atmosphere that contribute to warming the Earth by trapping heat- what is called the greenhouse effect. Because the atmosphere is such a good absorber of longwave infrared, it effectively forms a one-way blanket over Earth's surface. Visible and near-visible radiation from the Sun easily gets through, but thermal radiation from the surface can't easily get back out. When the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is larger, more heat is trapped, and the Earth heats up. The major natural greenhouse gases are water vapor, carbon dioxide, and ozone. Other greenhouse gases include, but are not limited to: methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, and chlorofluorocarbons.

Grypania are fossils of what appear to have been photosynthetic alga. They occur in rocks as old as 2.1 billion years.

Grypania are fossils of what appear to have been photosynthetic alga. They occur in rocks as old as 2.1 billion years.

A Hadley cell is a closed circulation cell in which hot moist air rises at the equator and moves northward or southward depending on the hemisphere and descends at more northerly latitudes. The major driving force of atmospheric circulation in the tropical regions is solar heating. Because of the Earth's 23.5 ° axial tilt, the sun is never more than a few tens of degrees from directly overhead at noon in the tropics; as a consequence, incident solar radiation provides maximum energy at the equator. This heat is largely transported into the atmosphere as latent heat via convection in daily thunderstorms that form in this weather belt.

As the air travels northward it loses heat, and at about 30° north/south

of the equator, it begins to descend. As it descends it is compressed,

increases

in temperature from adiabatic heating and thus the relative humidity decreases,

so skies in this high-pressure weather regime tend to be cloud-free, and windless

days are common. This region marks the zone of separation between the Hadley

cell and another circulation cell, the temperate zone Ferrel cell, and is known

as the "horse

latitudes".

According to the story, in times when ship's captains relied upon the wind

to reach their

destinations, finding themselves becalmed was usually bad news for any horses

aboard, which were thrown overboard in order to conserve precious water.

W. Brian Harland (1917 – 2003) was an eminent geologist at Cambridge University, England. He played an important early role in the advocation of the theory of continental drift and making the first observations of the global occurrence of glaciation which were to form the foundations of Snowball Earth theory. He was also a foremost figure in the ongoing maintenance of the International Geologic timescale.

He also spent 43 field seasons in the geological mapping of the Polar archipelago of Spitsbergen beginning in 1938 and lasting through to the 1980s, leading 29 expeditions. The ice field "Harlandisen" on the main island of Svalbard is named in his honour.

Horodyskia is a complex megafossil found in rocks 1.5 billion years old in Montana and western Australia. They are horizontal tubes from which closely-spaced spheres develop to form a "string of beads". Because all beads are similar along a string, Horodyskia is judged to be a colonial organism. It had a tough outer protective layer, which implies a softer interior, and therefore tissue differentiation. You can learn more about these interesting fossils here.

Walter Howchin was born in England in 1845 and developed an early interest in geology. He migrated to Australia in 1881 and spend several years as secretary of the Adelaide Childrens' Hospital before taking up a position as geology teacher at the School of Mines. In 1902 he was appointed Lecturer in Geology and Palaeontology at the University of Adelaide and continued teaching for 19 years. He was awarded the title of Honorary Professor in 1918. His contributions to geological knowledge, especially of the glacial period, earned him an international reputation and respect.

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure in a planet's surface from which geothermally heated water issues. Hydrothermal vents are commonly found in places that are also volcanically active, where hot magma is relatively near the planet's surface.

Hydrothermal vents are abundant on Earth because it is both geologically active and has large amounts of water on its surface. Common land types include hot springs, fumaroles and geysers. The most famous hydrothermal vent system on land is probably Yellowstone National Park in the United States.

In 1949 a deep water survey reported anomalously hot brines in the central portions of the Red Sea. Later work in the 1960s confirmed the presence of hot, 60 °C, saline brines and associated metaliferous muds. The hot solutions were emanating from an active subseafloor rift. The highly saline character of the waters were not hospitable to living organisms. The brines and associated muds are currently under investigation as a source of mineable precious and base metals.

Submarine hydrothermal vents (black smokers) were discovered along the East Pacific Rise in 1977. Despite their inaccessible location on ocean floors, many have been thoroughly mapped and explored. Relative to the majority of the deep sea, the areas around hydrothermal vents are biologically productive, often hosting complex communities fueled by the chemicals dissolved in the vent fluids. Chemosynthetic archaea form the base of the food chain, supporting diverse organisms such as giant tube worms, clams, and shrimp.

The water that issues from hydrothermal vents consists mostly of ground water that has percolated down into hot regions from the surface, but it also commonly contains some portion of primordial water that originated deep underground and is only now surfacing for the first time. The proportion varies from location to location.

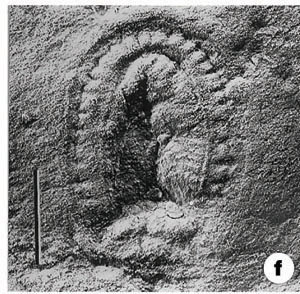

Kimberella is a fossil animal from the Ediacaran fauna.

This fossil varies from 3mm to 10 cm in size. It is oval in shape with larger ones being elongated more. The long axis has a raised ridge, and the edge is crenulated or scalloped with 44 lobes, though some always appear missing.

The organism this fossil represents is believed to be a bilaterian organism, with bilateral symmetry. As such it is the earliest known bilaterian animal. It may represent the ancestor of all bilaterian animals, including humans, or may be a lophotrochozoan ancestor. It has been interpreted as a mollusk with a non mineralised shell.

Kimberella may have left trace fossils consisting of long trails that have been found in the Ediacaran strata.

This species was first described by Glaessner and Daily in 1959. Its fossils are found both in the Ediacara Hills of South Australia and in the White Sea region of Russia.

Kimberella is a fossil animal from the Ediacaran fauna.

This fossil varies from 3mm to 10 cm in size. It is oval in shape with larger ones being elongated more. The long axis has a raised ridge, and the edge is crenulated or scalloped with 44 lobes, though some always appear missing.

The organism this fossil represents is believed to be a bilaterian organism, with bilateral symmetry. As such it is the earliest known bilaterian animal. It may represent the ancestor of all bilaterian animals, including humans, or may be a lophotrochozoan ancestor. It has been interpreted as a mollusk with a non mineralised shell.

Kimberella may have left trace fossils consisting of long trails that have been found in the Ediacaran strata.

This species was first described by Glaessner and Daily in 1959. Its fossils are found both in the Ediacara Hills of South Australia and in the White Sea region of Russia.

Leiosphere is a common name without taxonomic implications for thin-walled smooth or slightly ornamented spherical microalgae. The botanical affinities of leiospheres are unknown.

Simple, thin-walled spheres, like Leiosphaeridia, may develop in a variety of algal taxa. When found as fossil remains, these spheres may appear morphologically undistinguishable, despite they are naturally unrelated.

Many acid resistant spherical microfossils have been recorded in sediments ranging from the early pre-Cambrian to Recent. They are widespread in pre-Cambrian and Paleozoic deposits.

The taxonomic classification is hazardous and complex in this group because the only features for classification are wall structure, ornamentation, and opening mechanisms. These features are not sufficient for a classification to modern algal taxa above the rank of species—not even at the rank of class.

The Lophotrochozoa are a diverse bilaterian group of animals that have a feeding apparatus known as a lophophore (such as Bryozoans, Brachiopods and the Phoronids) and a trochophore larvae (which have two bands of cilia around their middle), such as found in the annelids and molluscs). Some members of this group are assigned based on genetic studies including RNA and Hox genes. View where lophotrochozoa sit in the tree of life here.

Methanogens are Archaea that produce methane as a metabolic by-product. They are common in wetlands, where they are responsible for marsh gas, and in the guts of animals such as ruminants and human, where they are responsible for flatulence. They are also common in soils in which the oxygen has been depleted. Others are extremophiles, found in environments such as hot springs and submarine hydrothermal vents. There are over 50 species of methanogens.

Methanogens are anaerobic: all methanogens are rapidly killed in the presence of oxygen. Some, called hydrotrophic, use carbon dioxide as a source of carbon and hydrogen as a source of energy (hydrogen functions as a reducing agent). Some of the carbon dioxide is reacted with the hydrogen to produce methane, which produces a proton motive force across a membrane, which is used to generate ATP. In contrast, plants and algae use water as their reducing agent. Other methanogens use acetate (CH3COO-) as a source of carbon and a source of energy. This type of metabolism is referred to as "acetotrophic" or "aceticlastic," breaking down acetate to produce carbon dioxide and methane. Other methanogens are able to utilize methylated compounds such as methylamines, methanol, and methanethiol as well.

Ecologically, methanogens play the vital role in anaerobic environments of removing excess hydrogen and fermentation products that have been produced by other forms of anaerobic respiration. Methanogens typically thrive in environments in which all other electron acceptors (such as oxygen, nitrate, sulfate, and trivalent iron) have been depleted.

Methanogens have been discovered in two extreme environments on Earth - buried under kilometres of ice in Greenland and living in hot, dry desert soil. Live microbes making methane were found in a glacial ice core sample retrieved from three kilometres under Greenland by researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, US. Another study discovered methanogens in a harsh environment on Earth. Researchers studied dozens of soil and vapour samples from five different desert environments in Utah, Idaho and California in the US, and in Canada and Chile. Of these, five soil samples and three vapour samples from the vicinity of the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah were found to have signs of viable methanogens.

Several massive worldwide glaciations occurred during the Neoproterozoic era including the Sturtian (~700 Ma) and Marinoan (635Ma) glaciations, the most severe the Earth has ever known. These are believed to have been so severe as to bring icecaps to the equator, leading to a state known as "Snowball Earth".

Moraine is the general term for debris of all sorts that was transported by glaciers or ice sheets. The following are common types of moraine:

Lateral moraine: The talus and other material from the sides of a glacial valley accumulated on the glacier and carried along with it. The mass of debris distributed along the lateral edges of the glacier are thus called lateral moraine. In the case of valley glaciers which have disappeared, their former existence may often be proved by the traces of lateral moraines left along the sides of the valley.

Medial moraine: If one or more tributary glaciers coalesce with the main glacier the lateral moraines unite to form trains of debris on the surface of the glacier at or near its center, called medial moraines.

Terminal moraine: When balance is maintained between the melting of a glacier and its forward advance, the debris carried on (supraglacial), within (englacial), and dragged along the bottom (subglacial) is deposited at that point and builds up a heterogeneous mass of the transported material called the terminal moraine. If a glacier is slowly retreating and makes successive halts farther and farther up the valley, a series of terminal moraines are formed which are spoken of as recessional moraines.

Interlobate moraine: If large glaciers and continental ice sheets advance irregularly so that their margins are lobate, when the margins retreat by melting the resulting terminal moraines of boulders, clay, and sand simulate the original interlobate shape of the glacier or glaciers, and therefore such moraines are called interlobate.

Ground moraine: When a valley glacier melts completely away the debris carried on or within it are dropped on the valley floor, forming a deposit called ground moraine. The ground moraine from the melting of the great Pleistocene ice sheets is usually spoken of as till.

The Neoproterozoic is the geological era from 1000 Ma to 542 Ma (million years ago). The Neoproterozoic includes rocks from one of the most interesting time periods in the geological record, during which the Earth was hit by the most severe glaciations known, and the earliest evidence for multicelled life occur (the Ediacaran Period). The Neoproterozoic is the final part of Precambrian time and is the youngest of three divisions of the Proterozoic.

Paleomagnetism refers to the orientation of the Earth's magnetic field as it is preserved in various magnetic iron-bearing minerals in rocks. The study of paleomagnetism has demonstrated that the Earth's magnetic field has changed both in orientation and intensity through time.

Two aspects of paleomagnetism are especially important:

- Polar wandering: the magnetic poles are constantly shifting relative to the axis of rotation. This is responsible for the shifting magnetic declination required for compass work and orienteering.

- Magnetic polarity reversals: periodically, the Earth's magnetic field reverses polarity such that the north pole becomers south and vice-versa. The reversals have occurred at irregular intervals throughout the Earth's history.

Paleomagnetic evidence, both reversals and polar wandering data, was instrumental in verifying the theories of continental drift and plate tectonics in the 1960s and 70s.

pH is a measure of the activity of hydrogen ions (H+) in a solution and, therefore, its acidity or alkalinity. Aqueous solutions with pH values lower than 7 are considered acidic, while pH values higher than 7 are considered alkaline. Note that pH is measured on a logarithmic scale thus a liquid with a pH of 8 is actually 10 times as acidic as one with a pH of 7.

Phototrophs, or photoautotrophs as they are sometimes called, are photosynthetic algae, fungi, bacteria and cyanobacteria which build up carbon dioxide and water into organic cell materials using energy from sunlight. One product of this process is starch, which is a storage or reserve form of carbon, which can be used when light conditions are too poor to satisfy the immediate needs of the organism. Photosynthetic bacteria have a substance called bacteriochlorophyll, live in lakes and pools, and use the hydrogen from hydrogen sulfide instead of from water, for the chemical process. (The bacteriochlorophyll pigment absorbs light in the extreme UV and infra-red parts of the spectrum which is outside the range used by normal chlorophyll). Purple and green sulfur bacteria use light, carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide from anaerobic decay, to produce carbohydrate, sulfur and water. Cyanobacteria live in fresh water, seas, soil and lichen, and use a plant-like photosynthesis which releases oxygen as a byproduct.

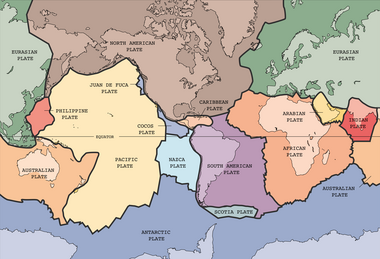

Plate tectonics (from the Greek word=tekton for "one who constructs",

) is a theory of geology developed to explain the phenomenon of continental drift,

and is currently the theory accepted by the vast majority of scientists, since

the movement of the plates can actually be measured. The main features of plate

tectonics are

Plate tectonics (from the Greek word=tekton for "one who constructs",

) is a theory of geology developed to explain the phenomenon of continental drift,

and is currently the theory accepted by the vast majority of scientists, since

the movement of the plates can actually be measured. The main features of plate

tectonics are

- The Earth's surface is covered by a series of crustal plates.

- The ocean floors are continually, moving, spreading from the center, sinking at the edges, and being regenerated.

- Convection currents beneath the plates move the crustal plates in different directions.

- The source of heat driving the convection currents is radioactivity deep in the Earth.

Prokaryotes (from Old Greek pro- before + karyon nut, referring to the cell nucleus) are organisms without a cell nucleus (karyon), or indeed any other membrane-bound organelles, in most cases unicellular (in rare cases, multicellular). This is in contrast to eukaryotes, organisms that have cell nuclei and may be variously unicellular or multicellular. The difference between the structure of prokaryotes and eukaryotes is so great that it is considered to be the most important distinction among groups of organisms. Most prokaryotes are bacteria, and the two terms are often treated as synonyms. However, some have proposed dividing prokaryotes into the Bacteria and Archaea (originally Eubacteria and Archaebacteria) because of the significant genetic differences between the two.

This Phylogenetic Tree based on rRNA data, shows the separation of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes.

The Proterozoic is the younger of the two Precambrian eons and ranges from 2500Ma to 542Ma. It is divided into three geologic periods (era) called, from oldest to youngest: Paleoproterozoic, Mesoproterozoic, and Neoproterozoic

| Precambrian | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hadean eon | Archean eon | Proterozoic eon | Phanerozoic eon |

Protostomes (from the Greek=first the mouth) are a taxon of animals. Together with the deuterostomes and a few smaller phyla, they make up the Bilateria, mostly comprising animals with bilateral symmetry and three germ layers. The major distinctions between deuterostomes and protostomes are found in embryonic development. In protostomes the mouth forms at the site of the blastopore, and the anus forms as a second opening; whereas the anul forms first in deuterostomes.

A psychrophile is a type of extremophilic organism which thrives at cold temperatures, that are the usual condition on Earth, as more than 90% of our planet surface enjoys temperatures lower than 15°C. They can be contrasted with thermophiles, which thrive at unusually hot temperatures.

There are generally considered to be two groups of psychrophiles: "classic" psychrophiles, and a second group that are sometimes referred to as psychrotrophs by food microbiologists. Classic psychrophiles are those organisms having a growth temperature optimum of 15°C or lower - and do not grow in a climate beyond a maximum temperature of 20°C. They are largely found in icy places (such as in Antarctica) or at the freezing bottom of the ocean floor. This separation is becoming fuzzy as more organisms with a fairly large growth temperature range are discovered.

Hans Henrik Reusch (5 September 1852 – ?), Norwegian geologist, was born at Bergen. He was educated at Christiania, Leipzig and Heidelberg, and graduated Ph.D. at Christiania in 1883.

He joined the Geological Survey of Norway in 1875, and became its Director in 1888. He is distinguished for his research on the crystalline schists and the Palaeozoic rocks of Norway. He discovered Silurian fossils in the highly altered rocks of the Bergen region; and in 1891 he called attention to a Palaeozoic conglomerate of glacial origin in the Varanger Fjord, a view confirmed by Mr A. Strahan in 1896, who found glacial striations on the rocks beneath the ancient boulder-bed. Reusch has likewise thrown light on the later geological periods, on the Pleistocene glacial phenomena and on the sculpturing of the scenery of Norway. Among his separate publications were Silur fossiler og pressede Konglomerater (1882) and Det nordlige Norges Geologi (1891).

The Ring of Fire is a zone of volcanic eruptions that encircles the basin of the Pacific Ocean. It is shaped like a horseshoe and it is 40,000km long. It is associated with a nearly continuous series of oceanic trenches, island arcs, and volcanic mountain ranges.

The Ring of Fire is a zone of volcanic eruptions that encircles the basin of the Pacific Ocean. It is shaped like a horseshoe and it is 40,000km long. It is associated with a nearly continuous series of oceanic trenches, island arcs, and volcanic mountain ranges.

Sublimation of an element or substance is a conversion from the solid to the gaseous phases of matter, with no intermediate liquid stage.

Till is a general term for unsorted glacial sediment deposited directly by glaciers. Till is typically deposited at the ends and along the sides of a glacier.

In cases where till has been indurated or lithified by subsequent burial into solid rock, it is known as the sedimentary rock tillite. Matching beds of ancient tillites on opposite sides of the south Atlantic Ocean provided early evidence for continental drift and provided critical evidence for the Snowball Earth glaciation event.

Weathering is the process of decomposition and/or disintegration of rocks and their minerals in situ, that is, in place. It should not be confused with erosion, which is the movement of rocks and/or weathering products by water, wind, ice or gravity.